Philosophy

Education / Philosophy

Introduction

Knowledge

Initially, the term 'philosophy' referred to any body of knowledge. In this sense, philosophy is closely related to religion, mathematics, natural science, education, and politics. Though as of the 2000s it has been classified as a book of physics, Newton's Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy (1687) uses the term natural philosophy as it was understood at the time to encompass disciplines, such as astronomy, medicine and physics, that later became associated with sciences.

In the first part of his Academica 1, Cicero introduced the division of philosophy into logic, physics, and ethics, emulating Epicurus' division of his doctrine into canon, physics, and ethics.

In section thirteen of his Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers 1, Diogenes Laërtius (3rd century), the first historian of philosophy, established the traditional division of philosophical inquiry into three parts:

Natural philosophy (i.e. physics, from Greek: ta physika, lit. 'things having to do with physis [nature]') was the study of the constitution and processes of transformation in the physical world;

Moral philosophy (i.e. ethics, from êthika, 'having to do with character, disposition, manners') was the study of goodness, right and wrong, justice and virtue; and

Metaphysical philosophy (i.e. logic, from logikós, 'of or pertaining to reason or speech') was the study of existence, causation, God, logic, forms, and other abstract objects (meta ta physika, 'after the Physics').

This division is not obsolete but has changed: natural philosophy has split into the various natural sciences, especially physics, astronomy, chemistry, biology, and cosmology; moral philosophy has birthed the social sciences, while still including value theory (e.g. ethics, aesthetics, political philosophy, etc.); and metaphysical philosophy has given way to formal sciences such as logic, mathematics and philosophy of science, while still including epistemology, cosmology, etc.

Philosophical progress

Many philosophical debates that began in ancient times are still debated today. McGinn (1993) and others claim that no philosophical progress has occurred during that interval. Chalmers (2013) and others, by contrast, see progress in philosophy similar to that in science, while Brewer (2011) argued that "progress" is the wrong standard by which to judge philosophical activity.

Historical overview

In one general sense, philosophy is associated with wisdom, intellectual culture, and a search for knowledge. In this sense, all cultures and literate societies ask philosophical questions, such as "how are we to live" and "what is the nature of reality." A broad and impartial conception of philosophy, then, finds a reasoned inquiry into such matters as reality, morality, and life in all world civilizations.

Western philosophy

Main article: Western philosophy

Western philosophy is the philosophical tradition of the Western world, dating back to pre-Socratic thinkers who were active in 6th-century Greece (BCE), such as Thales (c. 624 – 546 BCE) and Pythagoras (c. 570 – 495 BCE) who practiced a 'love of wisdom' (Latin: philosophia)[32] and were also termed 'students of nature' (physiologoi).

Western philosophy can be divided into three eras:

Ancient Greek philosophy (Greco-Roman);

Medieval philosophy (Christian European); and

Ancient era

While our knowledge of the ancient era begins with Thales in the 6th century BCE, comparatively little is known about the philosophers who came before Socrates (commonly known as the pre-Socratics). The ancient era was dominated by Greek philosophical schools, which were significantly influenced by Socrates' teachings. Most notable among these were Plato, who founded the Platonic Academy, and his student Aristotle, who founded the Peripatetic school. Other ancient philosophical traditions included Cynicism, Stoicism, Skepticism and Epicureanism. Important topics covered by the Greeks included metaphysics (with competing theories such as atomism and monism), cosmology, the nature of the well-lived life (eudaimonia), the possibility of knowledge and the nature of reason (logos). With the rise of the Roman empire, Greek philosophy was also increasingly discussed in Latin by Romans such as Cicero and Seneca (see Roman philosophy).

Medieval era

Medieval philosophy (5th–16th centuries) is the period following the fall of the Western Roman Empire and was dominated by the rise of Christianity and hence reflects Judeo-Christian theological concerns as well as retaining a continuity with Greco-Roman thought. Problems such as the existence and nature of God, the nature of faith and reason, metaphysics, the problem of evil were discussed in this period. Some key Medieval thinkers include St. Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, Boethius, Anselm and Roger Bacon. Philosophy for these thinkers was viewed as an aid to Theology (ancilla theologiae) and hence they sought to align their philosophy with their interpretation of sacred scripture. This period saw the development of Scholasticism, a text critical method developed in medieval universities based on close reading and disputation on key texts. The Renaissance period saw increasing focus on classic Greco-Roman thought and on a robust Humanism.

Modern era

Early modern philosophy in the Western world begins with thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes and René Descartes (1596–1650). Following the rise of natural science, modern philosophy was concerned with developing a secular and rational foundation for knowledge and moved away from traditional structures of authority such as religion, scholastic thought and the Church. Major modern philosophers include Spinoza, Leibniz, Locke, Berkeley, Hume, and Kant.

19th-century philosophy (sometimes called late modern philosophy) was influenced by the wider 18th-century movement termed "the Enlightenment", and includes figures such as Hegel a key figure in German idealism, Kierkegaard who developed the foundations for existentialism, Nietzsche a famed anti-Christian, John Stuart Mill who promoted utilitarianism, Karl Marx who developed the foundations for communism and the American William James. The 20th century saw the split between analytic philosophy and continental philosophy, as well as philosophical trends such as phenomenology, existentialism, logical positivism, pragmatism and the linguistic turn (see Contemporary philosophy).

Middle Eastern philosophy

The regions of the fertile Crescent, Iran and Arabia are home to the earliest known philosophical Wisdom literature and is today mostly dominated by Islamic culture. Early wisdom literature from the fertile crescent was a genre which sought to instruct people on ethical action, practical living and virtue through stories and proverbs. In Ancient Egypt, these texts were known as sebayt ('teachings') and they are central to our understandings of Ancient Egyptian philosophy. Babylonian astronomy also included much philosophical speculations about cosmology which may have influenced the Ancient Greeks. Jewish philosophy and Christian philosophy are religio-philosophical traditions that developed both in the Middle East and in Europe, which both share certain early Judaic texts (mainly the Tanakh) and monotheistic beliefs. Jewish thinkers such as the Geonim of the Talmudic Academies in Babylonia and Maimonides engaged with Greek and Islamic philosophy. Later Jewish philosophy came under strong Western intellectual influences and includes the works of Moses Mendelssohn who ushered in the Haskalah (the Jewish Enlightenment), Jewish existentialism, and Reform Judaism.

Pre-Islamic Iranian philosophy begins with the work of Zoroaster, one of the first promoters of monotheism and of the dualism between good and evil. This dualistic cosmogony influenced later Iranian developments such as Manichaeism, Mazdakism, and Zurvanism.

After the Muslim conquests, Early Islamic philosophy developed the Greek philosophical traditions in new innovative directions. This Islamic Golden Age influenced European intellectual developments. The two main currents of early Islamic thought are Kalam which focuses on Islamic theology and Falsafa which was based on Aristotelianism and Neoplatonism. The work of Aristotle was very influential among the falsafa such as al-Kindi (9th century), Avicenna (980 – June 1037) and Averroes (12th century). Others such as Al-Ghazali were highly critical of the methods of the Aristotelian falsafa. Islamic thinkers also developed a scientific method, experimental medicine, a theory of optics and a legal philosophy. Ibn Khaldun was an influential thinker in philosophy of history.

In Iran, several schools of Islamic philosophy continued to flourish after the Golden Age and include currents such as Illuminationist philosophy, Sufi philosophy, and Transcendent theosophy. The 19th- and 20th-century Arab world saw the Nahda movement (literally meaning 'The Awakening'; also known as the 'Arab Renaissance'), which had a considerable influence on contemporary Islamic philosophy.

Indian philosophy

Main articles: Indian philosophy, Indonesian philosophy, and Eastern philosophy

Indian philosophy (Sanskrit: darśana, lit. 'point of view', 'perspective') refers to the diverse philosophical traditions that emerged since the ancient times on the Indian subcontinent. Jainism and Buddhism originated at the end of the Vedic period, while Hinduism emerged after the period as a fusion of diverse traditions.

Hindus generally classify these traditions as either orthodox (āstika) or heterodox (nāstika) depending on whether they accept the authority of the Vedas and the theories of brahman ('eternal', 'conscious', 'irreducible') and ātman ('soul', 'self', 'breathe') therein. The orthodox schools include the Hindu traditions of thought, while the heterodox schools include the Buddhist and the Jain traditions. Other schools include the Ajñana, Ājīvika, and Cārvāka which became extinct over their history.

Important Indian philosophical concepts shared by the Indian philosophies and virtues include:

dhárma ('that which upholds or supports');

karma (kárman, 'act', 'action', 'performance');

artha ('wealth', 'property');

kā́ma ('desire');

duḥkha ('suffering');

anitya (from Buddhist: anicca, 'impermanence');

dhyāna (or jhāna; 'meditation');

saṃnyāsa ('renunciation'), renouncing with or without monasticism or asceticism;

saṃsāra ('passage' or 'wandering'), various cycles of death and rebirth;

kaivalya ('separateness'), a state of mokṣa ('release', 'liberation', 'nirvana') from rebirth; and

ahiṃsā ('nonviolence').

Jain philosophy

Jain philosophy accepts the concept of a permanent soul (jiva) as one of the five astikayas (eternal, infinite categories that make up the substance of existence). The other four being dhárma, adharma, ākāśa ('space'), and pudgala ('matter').

The Jain thought separates matter from the soul completely, with two major subtraditions: Digambara ('sky dressed', 'naked') and Śvētāmbara ('white dressed'), along with several more minor traditions such as Terapanthi.

Asceticism is a major monastic virtue in Jainism. Jain texts such as the Tattvartha Sutra state that right faith, right knowledge and right conduct is the path to liberation.[49] The Jain thought holds that all existence is cyclic, eternal and uncreated. The Tattvartha Sutra is the earliest known, most comprehensive and authoritative compilation of Jain philosophy.

Buddhist philosophy

Buddhist philosophy begins with the thought of Gautama Buddha (fl. between 6th and 4th century BCE) and is preserved in the early Buddhist texts. It originated in India and later spread to East Asia, Tibet, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia, developing various traditions in these regions. Mahayana forms are the dominant Buddhist philosophical traditions in East Asian regions such as China, Korea and Japan. The Theravada forms are dominant in Southeast Asian countries, such as Sri Lanka, Burma and Thailand.

Because ignorance to the true nature of things is considered one of the roots of suffering (dukkha), Buddhist philosophy is concerned with epistemology, metaphysics, ethics and psychology. Buddhist philosophical texts must also be understood within the context of meditative practices which are supposed to bring about certain cognitive shifts.:8 Key innovative concepts include the four noble truths as an analysis of dukkha, anicca (impermanence), and anatta (non-self).

After the death of the Buddha, various groups began to systematize his main teachings, eventually developing comprehensive philosophical systems termed Abhidharma.:37 Following the Abhidharma schools, Mahayana philosophers such as Nagarjuna and Vasubandhu developed the theories of śūnyatā ('emptiness of all phenomena') and vijñapti-matra ('appearance only'), a form of phenomenology or transcendental idealism. The Dignāga school of pramāṇa ('means of knowledge') promoted a sophisticated form of Buddhist logico-epistemology.

There were numerous schools, sub-schools and traditions of Buddhist philosophy in India. According to Oxford professor of Buddhist philosophy Jan Westerhoff, the major Indian schools from 300 BCE to 1000 CE were::xxiv

The Sthavira schools which include: Sarvāstivāda, Sautrāntika, Vibhajyavāda (later known as Theravada in Sri Lanka), and Pudgalavāda.

The Mahayana schools, mainly the Madhyamaka, Yogachara, Tathāgatagarbha and Tantra.

After the disappearance of Buddhism from India, some of these philosophical traditions continued to develop in the Tibetan Buddhist, East Asian Buddhist and Theravada Buddhist traditions.

Hindu philosophies

The Vedas-based orthodox schools are a part of the Hindu traditions and they are traditionally classified into six darśanas: Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Samkhya, Yoga, Mīmāṃsā, and Vedanta. The Vedas as a knowledge source were interpreted differently by these six schools of Hindu philosophy, with varying degrees of overlap. They represent a "collection of philosophical views that share a textual connection," according to Chadha (2015). They also reflect a tolerance for a diversity of philosophical interpretations within Hinduism while sharing the same foundation.

Some of the earliest surviving Hindu mystical and philosophical texts are the Upanishads of the later Vedic period (1000–500 BCE). Hindu philosophers of the six schools developed systems of epistemology (pramana) and investigated topics such as metaphysics, ethics, psychology (guṇa), hermeneutics, and soteriology within the framework of the Vedic knowledge, while presenting a diverse collection of interpretations. These schools of philosophy accepted the Vedas and the Vedic concept of Ātman and Brahman, differed from the following Indian religions that rejected the authority of the Vedas:

Cārvāka, a materialism school that accepted the existence of free will.

Ājīvika, a materialism school that denied the existence of free will.

Buddhism, a philosophy that denies the existence of ātman ('unchanging soul', 'Self') and is based on the teachings and enlightenment of Gautama Buddha.

Jainism, a philosophy that accepts the existence of the ātman, but is based on the teachings of twenty-four ascetic teachers known as tirthankaras, with Rishabha as the first and Mahavira as the twenty-fourth.

The commonly named six orthodox schools over time led to what has been called the "Hindu synthesis" as exemplified by its scripture the Bhagavad Gita.

East Asian philosophy

East Asian philosophical thought began in Ancient China, and Chinese philosophy begins during the Western Zhou Dynasty and the following periods after its fall when the "Hundred Schools of Thought" flourished (6th century to 221 BCE). This period was characterized by significant intellectual and cultural developments and saw the rise of the major philosophical schools of China, Confucianism, Legalism, and Daoism as well as numerous other less influential schools. These philosophical traditions developed metaphysical, political and ethical theories such Tao, Yin and yang, Ren and Li which, along with Chinese Buddhism, directly influenced Korean philosophy, Vietnamese philosophy and Japanese philosophy (which also includes the native Shinto tradition). Buddhism began arriving in China during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), through a gradual Silk road transmission and through native influences developed distinct Chinese forms (such as Chan/Zen) which spread throughout the East Asian cultural sphere. During later Chinese dynasties like the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) as well as in the Korean Joseon dynasty (1392–1897) a resurgent Neo-Confucianism led by thinkers such as Wang Yangming (1472–1529) became the dominant school of thought, and was promoted by the imperial state.

In the Modern era, Chinese thinkers incorporated ideas from Western philosophy. Chinese Marxist philosophy developed under the influence of Mao Zedong, while a Chinese pragmatism under Hu Shih and New Confucianism's rise was influenced by Xiong Shili. Modern Japanese thought meanwhile developed under strong Western influences such as the study of Western Sciences (Rangaku) and the modernist Meirokusha intellectual society which drew from European enlightenment thought. The 20th century saw the rise of State Shinto and also Japanese nationalism. The Kyoto School, an influential and unique Japanese philosophical school developed from Western phenomenology and Medieval Japanese Buddhist philosophy such as that of Dogen.

African philosophy

African philosophy is philosophy produced by African people, philosophy that presents African worldviews, ideas and themes, or philosophy that uses distinct African philosophical methods. Modern African thought has been occupied with Ethnophilosophy, with defining the very meaning of African philosophy and its unique characteristics and what it means to be African.[76] During the 17th century, Ethiopian philosophy developed a robust literary tradition as exemplified by Zera Yacob. Another early African philosopher was Anton Wilhelm Amo (c. 1703–1759) who became a respected philosopher in Germany. Distinct African philosophical ideas include Ujamaa, the Bantu idea of 'Force', Négritude, Pan-Africanism and Ubuntu. Contemporary African thought has also seen the development of Professional philosophy and of Africana philosophy, the philosophical literature of the African diaspora which includes currents such as black existentialism by African-Americans. Some modern African thinkers have been influenced by Marxism, African-American literature, Critical theory, Critical race theory, Postcolonialism and Feminism.

Indigenous American philosophy

Indigenous-American philosophical thought consists of a wide variety of beliefs and traditions among different American cultures. Among some of U.S. Native American communities, there is a belief in a metaphysical principle called the 'Great Spirit' (Siouan: wakȟáŋ tȟáŋka; Algonquian: gitche manitou). Another widely shared concept was that of orenda ('spiritual power'). According to Whiteley (1998), for the Native Americans, "mind is critically informed by transcendental experience (dreams, visions and so on) as well as by reason." The practices to access these transcendental experiences are termed shamanism. Another feature of the indigenous American worldviews was their extension of ethics to non-human animals and plants.

In Mesoamerica, Aztec philosophy was an intellectual tradition developed by individuals called Tlamatini ('those who know something') and its ideas are preserved in various Aztec codices. The Aztec worldview posited the concept of an ultimate universal energy or force called Ōmeteōtl ('Dual Cosmic Energy') which sought a way to live in balance with a constantly changing, "slippery" world.

The theory of Teotl can be seen as a form of Pantheism.[80] Aztec philosophers developed theories of metaphysics, epistemology, values, and aesthetics. Aztec ethics was focused on seeking tlamatiliztli ('knowledge', 'wisdom') which was based on moderation and balance in all actions as in the Nahua proverb "the middle good is necessary."

The Inca civilization also had an elite class of philosopher-scholars termed the Amawtakuna who were important in the Inca education system as teachers of religion, tradition, history and ethics. Key concepts of Andean thought are Yanantin and Masintin which involve a theory of “complementary opposites” that sees polarities (such as male/female, dark/light) as interdependent parts of a harmonious whole.

Women in philosophy

Although men have generally dominated philosophical discourse, women philosophers have engaged in the discipline throughout history. Ancient examples include Hipparchia of Maroneia (active c. 325 BCE) and Arete of Cyrene (active 5th–4th centuries BCE). Some women philosophers were accepted during the medieval and modern eras, but none became part of the Western canon until the 20th and 21st century, when many suggest that G.E.M. Anscombe, Hannah Arendt, Simone de Beauvoir, and Susanne Langer entered the canon.

In the early 1800s, some colleges and universities in the UK and US began admitting women, producing more female academics. Nevertheless, U.S. Department of Education reports from the 1990s indicate that few women ended up in philosophy, and that philosophy is one of the least gender-proportionate fields in the humanities, with women making up somewhere between 17% and 30% of philosophy faculty according to some studies.

Branches of philosophy

Philosophical questions can be grouped into various branches. These groupings allow philosophers to focus on a set of similar topics and interact with other thinkers who are interested in the same questions. The groupings also make philosophy easier for students to approach. Students can learn the basic principles involved in one aspect of the field without being overwhelmed with the entire set of philosophical theories.

Various sources present different categorical schemes. The categories adopted in this article aim for breadth and simplicity.

These five major branches can be separated into sub-branches and each sub-branch contains many specific fields of study:

Metaphysics and epistemology

Value theory

Science, logic, and mathematics

History of philosophy

These divisions are neither exhaustive, nor mutually exclusive. (A philosopher might specialize in Kantian epistemology, or Platonic aesthetics, or modern political philosophy). Furthermore, these philosophical inquiries sometimes overlap with each other and with other inquiries such as science, religion or mathematics.

Epistemology, metaphysics, and related branches

Epistemology

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that studies knowledge. Epistemologists examine putative sources of knowledge, including perceptual experience, reason, memory, and testimony. They also investigate questions about the nature of truth, belief, justification, and rationality.

One of the most notable epistemological debates in the early modern period was between empiricism and rationalism. Empiricism places emphasis on observational evidence via sensory experience as the source of knowledge. Empiricism is associated with a posteriori knowledge, which is obtained through experience (such as scientific knowledge). Rationalism places emphasis on reason as a source of knowledge. Rationalism is associated with a priori knowledge, which is independent of experience (such as logic and mathematics).

Philosophical skepticism, which raises doubts some or all claims to knowledge, has been a topic of interest throughout the history of philosophy. Philosophical skepticism dates back thousands of years to ancient philosophers like Pyrrho, and features prominently in the works of modern philosophers René Descartes and David Hume. Skepticism has remained a central topic in contemporary epistemological debates.

One central debate in contemporary epistemology is about the conditions required for a belief to constitute knowledge, which might include truth and justification. This debate was largely the result of attempts to solve the Gettier problem. Another common subject of contemporary debates is the regress problem, which occurs when trying to offer proof or justification for any belief, statement, or proposition. The problem is that whatever the source of justification may be, that source must either be without justification (in which case it must be treated as an arbitrary foundation for belief), or it must have some further justification (in which case justification must either be the result of circular reasoning, as in coherentism, or the result of an infinite regress, as in infinitism).

Metaphysics

Metaphysics is the study of the most general features of reality, such as existence, time, objects and their properties, wholes and their parts, events, processes and causation and the relationship between mind and body. Metaphysics includes cosmology, the study of the world in its entirety and ontology, the study of being.

A major point of debate is between realism, which holds that there are entities that exist independently of their mental perception and idealism, which holds that reality is mentally constructed or otherwise immaterial. Metaphysics deals with the topic of identity. Essence is the set of attributes that make an object what it fundamentally is and without which it loses its identity while accident is a property that the object has, without which the object can still retain its identity. Particulars are objects that are said to exist in space and time, as opposed to abstract objects, such as numbers, and universals, which are properties held by multiple particulars, such as redness or a gender. The type of existence, if any, of universals and abstract objects is an issue of debate.

Mind and language

Several subfields of philosophy are closely related to epistemology and metaphysics, most notably philosophy of mind and philosophy of language. All of these are sometimes grouped together as "core" fields in philosophy, although this terminology is now considered outdated. Philosophy of language explores the nature, origins, and use of language. Philosophy of mind explores the nature of the mind and its relationship to the body, as typified by disputes between materialism and dualism. In recent years, this branch has become related to cognitive science.

Value theory

Value theory (or axiology) is the major branch of philosophy that addresses topics such as goodness, beauty and justice. Value theory includes ethics, aesthetics, political philosophy, feminist philosophy, philosophy of law and more.

Ethics

Ethics, also known as moral philosophy, studies what constitutes good and bad conduct, right and wrong values, and good and evil. Its primary investigations include how to live a good life and identifying standards of morality. It also includes investigating whether or not there is a best way to live or a universal moral standard, and if so, how we come to learn about it. The main branches of ethics are normative ethics, meta-ethics and applied ethics.

The three main views in ethics about what constitute moral actions are:

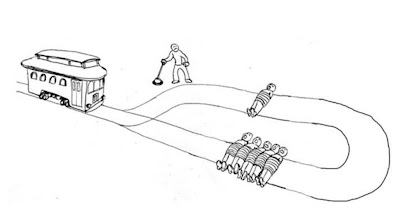

Consequentialism, which judges actions based on their consequences. One such view is utilitarianism, which judges actions based on the net happiness (or pleasure) and/or lack of suffering (or pain) that they produce.

Deontology, which judges actions based on whether or not they are in accordance with one's moral duty. In the standard form defended by Immanuel Kant, deontology is concerned with whether or not a choice respects the moral agency of other people, regardless of its consequences.

Virtue ethics, which judges actions based on the moral character of the agent who performs them and whether they conform to what an ideally virtuous agent would do.

Aesthetics

Aesthetics is the "critical reflection on art, culture and nature." It addresses the nature of art, beauty and taste, enjoyment, emotional values, perception and with the creation and appreciation of beauty. It is more precisely defined as the study of sensory or sensori-emotional values, sometimes called judgments of sentiment and taste. Its major divisions are art theory, literary theory, film theory and music theory. An example from art theory is to discern the set of principles underlying the work of a particular artist or artistic movement such as the Cubist aesthetic. The philosophy of film analyzes films and filmmakers for their philosophical content and explores film (images, cinema, etc.) as a medium for philosophical reflection and expression.

Political philosophy

Political philosophy is the study of government and the relationship of individuals (or families and clans) to communities including the state.[citation needed] It includes questions about justice, law, property and the rights and obligations of the citizen. Politics and ethics are traditionally linked subjects, as both discuss the question of how people should live together.

Other branches of value theory

Philosophy of law (aka jurisprudence): explores the varying theories explaining the nature and interpretation of laws.

Philosophy of education: analyzes the definition and content of education, as well as the goals and challenges of educators.

Feminist philosophy: explores questions surrounding gender, sexuality and the body including the nature of feminism itself as a social and philosophical movement.

Latino philosophy: explores systemic injustices, issues relating to the concept of borders, and power dynamics of sovereignty and decolonization.

Logic, science, and mathematics

Logic

Logic is the study of reasoning and argument. An argument is "a connected series of statements intended to establish a proposition." The connected series of statements are "premises" and the proposition is the conclusion. For example:

All humans are mortal. (premise)

Socrates is a human. (premise)

Therefore, Socrates is mortal. (conclusion)

Deductive reasoning is when, given certain premises, conclusions are unavoidably implied. Rules of inference are used to infer conclusions such as, modus ponens, where given “A” and “If A then B”, then “B” must be concluded.

Because sound reasoning is an essential element of all sciences, social sciences and humanities disciplines, logic became a formal science. Sub-fields include mathematical logic, philosophical logic, Modal logic, computational logic and non-classical logics. A major question in the philosophy of mathematics is whether mathematical entities are objective and discovered, called mathematical realism, or invented, called mathematical antirealism.

Philosophy of science

The philosophy of science explores the foundations, methods, history, implications and purpose of science. Many of its subdivisions correspond to specific branches of science. For example, philosophy of biology deals specifically with the metaphysical, epistemological and ethical issues in the biomedical and life sciences.

Philosophy of mathematics

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2020)

The philosophy of mathematics studies the philosophical assumptions, foundations and implications of mathematics.

History of philosophy

Further information: Philosophical progress and List of years in philosophy

Some contemporary philosophers specialize in studying one or more historical periods. The history of philosophy (study of a specific period, individual or school) should not be confused with the philosophy of history, a minor subfield most commonly associated with historicism as first defended in Hegel's Lectures on the Philosophy of History.

Other subfields

Philosophy of religion

Philosophy of religion deals with questions that involve religion and religious ideas from a philosophically neutral perspective (as opposed to theology which begins from religious convictions). Traditionally, religious questions were not seen as a separate field from philosophy proper, the idea of a separate field only arose in the 19th century.

Issues include the existence of God, the relationship between reason and faith, questions of religious epistemology, the relationship between religion and science, how to interpret religious experiences, questions about the possibility of an afterlife, the problem of religious language and the existence of souls and responses to religious pluralism and diversity.

Metaphilosophy

Metaphilosophy explores the aims of philosophy, its boundaries and its methods.

Applied philosophy

A variety of other academic and non-academic approaches have been explored. The ideas conceived by a society have profound repercussions on what actions the society performs. Weaver argued that ideas have consequences.

Philosophy yields applications such as those in ethics—applied ethics in particular—and political philosophy. The political and economic philosophies of Confucius, Sun Tzu, Chanakya, Ibn Khaldun, Ibn Rushd, Ibn Taymiyyah, Machiavelli, Leibniz, Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, Marx, Tolstoy, Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. have been used to shape and justify governments and their actions. Progressive education as championed by Dewey had a profound impact on 20th-century US educational practices. Descendants of this movement include efforts in philosophy for children, which are part of philosophy education. Clausewitz's political philosophy of war has had a profound effect on statecraft, international politics and military strategy in the 20th century, especially around World War II. Logic is important in mathematics, linguistics, psychology, computer science and computer engineering.

Other important applications can be found in epistemology, which aid in understanding the requisites for knowledge, sound evidence and justified belief (important in law, economics, decision theory and a number of other disciplines). The philosophy of science discusses the underpinnings of the scientific method and has affected the nature of scientific investigation and argumentation. Philosophy thus has fundamental implications for science as a whole. For example, the strictly empirical approach of B.F. Skinner's behaviorism affected for decades the approach of the American psychological establishment. Deep ecology and animal rights examine the moral situation of humans as occupants of a world that has non-human occupants to consider also. Aesthetics can help to interpret discussions of music, literature, the plastic arts and the whole artistic dimension of life. In general, the various philosophies strive to provide practical activities with a deeper understanding of the theoretical or conceptual underpinnings of their fields.

The relationship between "X" and the "philosophy of X" is often intensely debated. Richard Feynman argued that the philosophy of a topic is irrelevant to its primary study, saying that "philosophy of science is as useful to scientists as ornithology is to birds."[citation needed] Curtis White (2014), by contrast, argued that philosophical tools are essential to humanities, sciences and social sciences.

Society

Many inquiries outside of academia are philosophical in the broad sense. Novelists, playwrights, filmmakers, and musicians, as well as scientists and others engage in recognizably philosophical activity.

Some of those who study philosophy become professional philosophers, typically by working as professors who teach, research and write in academic institutions. However, most students of academic philosophy later contribute to law, journalism, religion, sciences, politics, business, or various arts. For example, public figures who have degrees in philosophy include comedians Steve Martin and Ricky Gervais, filmmaker Terrence Malick, Pope John Paul II, Wikipedia co-founder Larry Sanger, technology entrepreneur Peter Thiel, Supreme Court Justice Stephen Bryer and vice presidential candidate Carly Fiorina.

Recent efforts to avail the general public to the work and relevance of philosophers include the million-dollar Berggruen Prize, first awarded to Charles Taylor in 2016.

Professional philosophy

Germany was the first country to professionalize philosophy. The doctorate of philosophy (PhD) developed in Germany as the terminal Teacher's credential in the mid 17th century. At the end of 1817, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel was the first philosopher to be appointed Professor by the State, namely by the Prussian Minister of Education, as an effect of Napoleonic reform in Prussia. In the United States, the professionalization grew out of reforms to the American higher-education system largely based on the German model.

Within the last century, philosophy has increasingly become a professional discipline practiced within universities, like other academic disciplines. Accordingly, it has become less general and more specialized. In the view of one prominent recent historian: "Philosophy has become a highly organized discipline, done by specialists primarily for other specialists. The number of philosophers has exploded, the volume of publication has swelled, and the subfields of serious philosophical investigation have multiplied. Not only is the broad field of philosophy today far too vast to be embraced by one mind, something similar is true even of many highly specialized subfields." Some philosophers argue that this professionalization has negatively affected the discipline.

The end result of professionalization for philosophy has meant that work being done in the field is now almost exclusively done by university professors holding a doctorate in the field publishing in highly technical, peer-reviewed journals. While it remains common among the population at large for a person to have a set of religious, political or philosophical views that they consider their "philosophy", these views are rarely informed by or connected to the work being done in professional philosophy today. Furthermore, unlike many of the sciences for which there has come to be a healthy industry of books, magazines, and television shows meant to popularize science and communicate the technical results of a scientific field to the general populace, works by professional philosophers directed at an audience outside the profession remain rare. Books such as Harry Frankfurt's On Bullshit and Michael Sandel's Justice: What's the Right Thing to Do? hold the distinction, uncommon among contemporary works, of having been written by professional philosophers while also being directed at (and ultimately popular among) a broader audience of non-philosophers. Both works became New York Times bestsellers.

Philosophy contrasted with other disciplines

Natural science

Originally the term "philosophy" was applied to all intellectual endeavors. Aristotle studied what would now be called biology, meteorology, physics, and cosmology, alongside his metaphysics and ethics. Even in the eighteenth century physics and chemistry were still classified as "natural philosophy", that is, the philosophical study of nature. Today these latter subjects are popularly referred to as sciences, and as separate from philosophy. But the distinction is not clear; some philosophers still contend that science retains an unbroken — and unbreakable — link to philosophy.

More recently, psychology, economics, sociology, and linguistics were once the domain of philosophers insofar as they were studied at all, but now have only a weaker connection with the field. In the late twentieth century cognitive science and artificial intelligence could be seen as being forged in part out of "philosophy of mind."

Philosophy is done primarily through self-reflection and critical thinking. It does not tend to rely on experiment. However, in some ways philosophy is close to science in its character and method; some analytic philosophers have suggested that the method of philosophical analysis allows philosophers to emulate the methods of natural science; Quine holds that philosophy does no more than clarify the arguments and claims of other sciences. This suggests that philosophy might be the study of meaning and reasoning generally; but some still would claim either that this is not a science, or that if it is it ought not to be pursued by philosophers.

All these views have something in common: whatever philosophy essentially is or is concerned with, it tends on the whole to proceed more "abstractly" than most (or most other) natural sciences. It does not depend as much on experience and experiment, and does not contribute as directly to technology. It clearly would be a mistake to identify philosophy with any one natural science; whether it can be identified with science very broadly construed is still an open question.

This is an active discipline pursued by both trained philosophers and scientists. Philosophers often refer to, and interpret, experimental work of various kinds (as in philosophy of physics and philosophy of psychology), but such branches of philosophy aim at philosophical understanding of experimental work. Philosophers do not perform experiments and formulate scientific theories qua philosophers.

Theology and religious studies

Like philosophy, most religious studies are not experimental. Parts of theology, including questions about the existence and nature of gods, clearly overlap with philosophy of religion. Aristotle considered theology a branch of metaphysics, the central field of philosophy, and most philosophers before the twentieth century have devoted significant effort to theological questions. So the two are not unrelated. But other parts of religious studies, such as the comparison of different world religions, can be easily distinguished from philosophy in just the way that any other social science can be distinguished from philosophy. These are closer to history and sociology, and involve specific observations of particular phenomena, here particular religious practices.

The empiricist tradition in modern philosophy often held that religious questions are beyond the scope of human knowledge, and many have claimed that religious language is literally meaningless: there are not even questions to be answered. Some philosophers have felt that these difficulties in evidence were irrelevant, and have argued for, against, or just about religious beliefs on moral or other grounds.

Mathematics

The philosophy of mathematics is a branch of philosophy of science; but in many ways mathematics has a special relationship to philosophy. This is because the study of logic is a central branch of philosophy, and mathematics is a paradigmatic example of logic. In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, logic made great advances, and mathematics has been proven to be reducible to logic (at least, to first-order logic with some set theory). The use of formal, mathematical logic in philosophy now resembles the use of mathematics in science, although it is not as frequent.

Comments

Post a Comment